Supreme Court Feed

Updates on the latest opinions, orders, and decisions.

-

Merits Docket

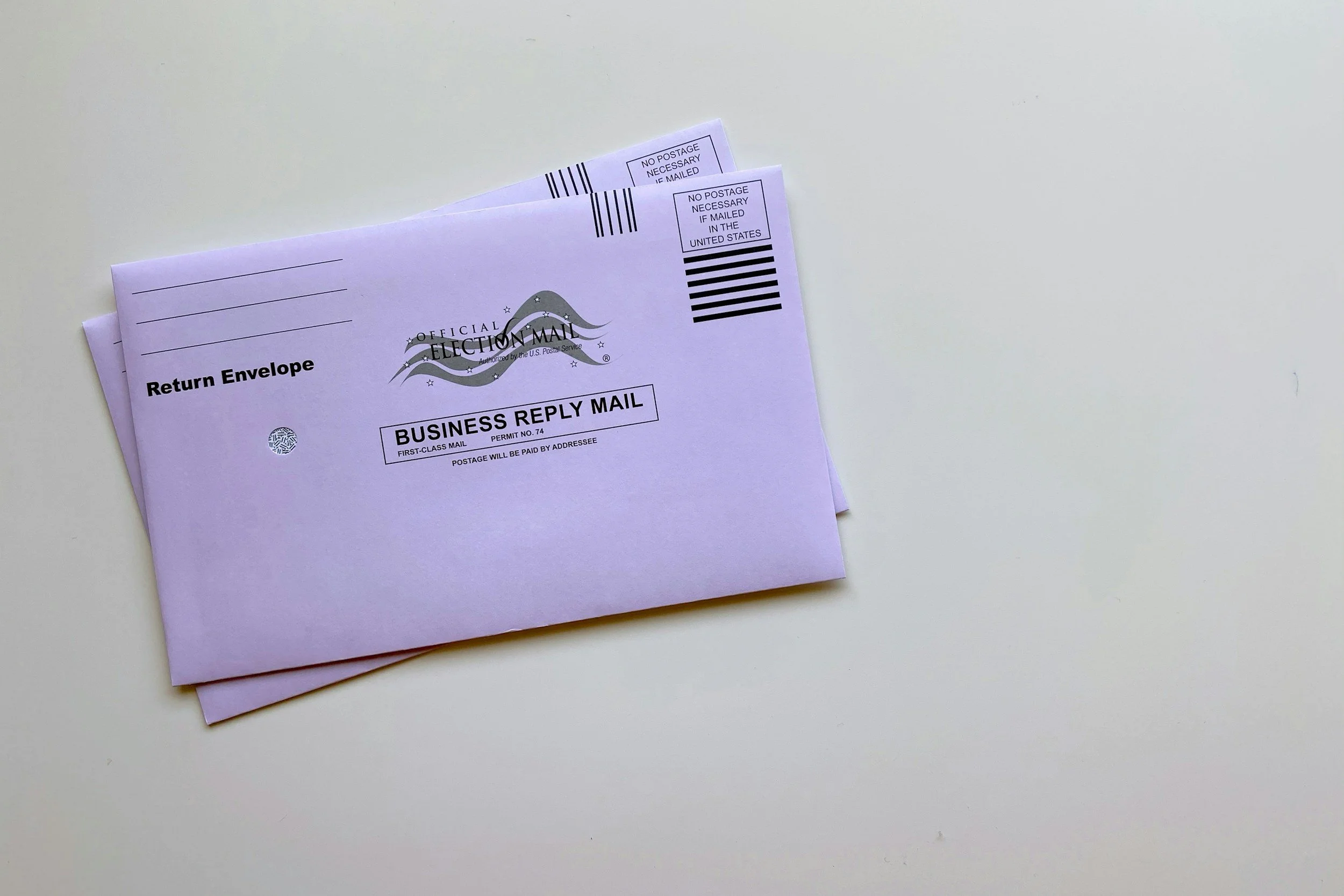

- Feb 14, 2026 Watson v. Republican National Committee: SCOTUS Set to Rule on Mail-In Ballot Access in 2026

- Feb 14, 2026 SCOTUS After Hours: Villarreal v. Texas and the Struggle to Define Permissible Consultation

- Jan 19, 2026 Noem v. Al Otro Lado

- Jan 4, 2026 Hencely v. Fluor Corporation: When Preemption Becomes Immunity

- Jan 4, 2026 Trump v. Barbara Re. Certiorari Granted December 5, 2025

- Nov 19, 2025 United States v. Hemani Re. Certiorari Granted October 20, 2025

- Nov 19, 2025 Revisiting Presidential Tariff Powers: From Yoshida to Learning Resources v. Trump

- Nov 19, 2025 Keathley v. Buddy Ayers Construction: The Cost of Bankruptcy Nondisclosure

- Nov 19, 2025 Bowe v. United States

- Nov 5, 2025 Louisiana v. Callais: What the Supreme Court’s Latest Voting Rights Debate Really Means

- Nov 4, 2025 Case v. Montana

- Oct 28, 2025 A 60-Year Grievance: Exxon Takes on Sovereign Immunity; Exxon Mobil Corp. v. Corporación Cimex

- Oct 8, 2025 Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton: The Complicated Role of Technology in the Law

- May 5, 2025 Cert. Granted in Chiles v. Salazar: A Case Concerning Conversion Therapy Bans

-

Emergency Docket

- Jan 30, 2026 Trump v. Illinois: Presidential Power to Federalize the National Guard During Domestic Unrest

- Jan 4, 2026 Duran v. United States: Justice Right Out of Reach

- Nov 19, 2025 Rollins v. Rhode Island State Council of Churches Re: November 11, 2025

- Nov 12, 2025 Trump v. Slaughter Re: Order Issued September 22, 2025

- Oct 16, 2025 Trump v. Cook and the Future of the Federal Reserve’s Independence

- Oct 14, 2025 Trump v. Orr Re: October 7, 2025

- Oct 8, 2025 Bessent v Dellinger Re: Order Issued February 21, 2025

-

Court Decisions

- Mar 8, 2026 Learning Resources, Inc v. Trump - Gorsuch Goes Renegade: The Champion of the Major Question’s Doctrine

- Apr 16, 2025 Trump v. United States: Is the Outrage Warranted?

- Apr 16, 2025 Andrew v. White

- Apr 16, 2025 On Facebook, Inc. v. Amalgamated Bank

- Apr 16, 2025 EMD Sales, Inc. v. Carrera: Preserving the Integrity of the FLSA